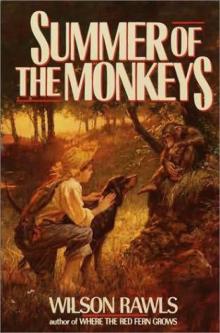

Summer of the Monkeys Read Online Pdf

Summer of the Monkeys

Wilson Rawls

Yearling (1976)

* * *

Rating: ★★★★☆

Tags: Historical, Classics, Take chances, Young Adult, Childrens

The last affair a fourteen-twelvemonth-sometime male child expects to discover along an old Ozark river bottom is a tree full of monkeys. Jay Berry Lee'southward grandpa had an caption, of course--every bit he did for almost things. The monkeys had escaped from a traveling circus, and there was a handsome advantage in store for anyone who could catch them. Grandpa said there wasn't whatever animal that couldn't exist caught somehow, and Jay Berry started out believing him . . .

Merely by the stop of the "summer of the monkeys," Jay Berry Lee had learned a lot more than he e'er bargained for--and not simply about monkeys. He learned about faith, and wishes coming truthful, and knowing what it is you really desire. He even learned a piddling about growing upwardly . . .

This novel, set in rural Oklahoma around the turn of the century, is a heart-warming family story--total of rich detail and delightful characters--about a time and place when miracles were actually the simplest of things...

From the Merchandise Paperback edition.

Amazon.com Review

Jay Drupe Lee is happy until the summer he is fourteen years quondam and discovers monkeys living in the creek bottoms near his parents' homestead. Ready in the late 1800s, Summer of the Monkeys traces the boy's adventures as he attempts to capture 29 monkeys that have (it turns out) escaped from the circus. With somewhat dubious help from his granddaddy, and over the objections of his mother, Jay goes about discovering that monkeys are much smarter and harder to catch than he thought possible. Woven into this story is a second theme about his physically disabled sister and the family unit's attempts to detect coin for an operation. As funny and touching equally Wilson Rawls'southward Where the Cherry-red Fern Grows, this book volition entreatment to the young reader who has always wished for the freedom to run wild through the woods with cipher more pressing to practice than notice some other rabbit hole--or escaped monkey. (Ages 12 and older) --Richard Farr

From the Publisher

The last thing a xiv-year-old boy expects to discover forth an onetime Ozark river bottom is a tree total of monkeys. Jay Berry Lee'due south grandpa had an explanation, of course--equally he did for most things. The monkeys had escaped from a traveling circus, and there was a handsome reward in store for anyone who could catch them. Gramps said there wasn't any animal that couldn't be caught somehow, and Jay Berry started out assertive him . . .

But by the end of the "summer of the monkeys," Jay Berry Lee had learned a lot more he e'er bargained for--and not just about monkeys. He learned about faith, and wishes coming truthful, and knowing what it is yous really desire. He even learned a little virtually growing up . . .

This novel, set in rural Oklahoma around the plough of the century, is a middle-warming family story--full of rich detail and delightful characters--about a time and place when miracles were really the simplest of things . . .

For more than forty years,

Yearling has been the leading name in classic and award-winning literature for young readers.

Yearling books feature children'southward favorite authors and characters,

providing dynamic stories of risk,

humor, history, mystery, and fantasy.

Trust Yearling paperbacks to entertain,

inspire, and promote the love of reading in all children.

OTHER YEARLING BOOKS YOU Will Bask

WHERE THE RED FERN GROWS, Wilson Rawls

LILY'South CROSSING, Patricia Reilly Giff

THE BLACK PEARL, Scott O'Dell

FROZEN STIFF, Sherry Shahan

THE WITCHES OF WORM, Zilpha Keatley Snyder

ALIDA'S Song, Gary Paulsen

BLACKWATER BEN, William Durbin

HOLES, Louis Sachar

THE INCREDIBLE JOURNEY, Sheila Burnford

BOYS AGAINST GIRLS, Phyllis Reynolds Naylor

Published by Yearling, an imprint of Random House Children's Books a division of Random Firm, Inc., New York

Copyright © 1976 past Woodrow Wilson Rawls

All rights reserved. No part of this volume may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by whatsoever information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher, except where permitted past law. For information address Bantam Books.

Yearling and the jumping equus caballus design are registered trademarks of Random Business firm, Inc.

Visit the states on the Web! www.randomhouse.com/kids

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at world wide web.randomhouse.com/teachers

eISBN: 978-0-307-78155-0

Reprinted by organisation with Runted Books

v3.i

Contents

Cover

Other Books by This Author

Title Folio

Copyright

Chapter One

Affiliate 2

Chapter Three

Affiliate Iv

Affiliate Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Viii

Affiliate Nine

Chapter X

Affiliate 11

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter 16

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Xviii

Chapter 19

About the Author

All the characters in this book are fictitious and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely casual.

one

Upward until I was 14 years old, no boy on earth could accept been happier. I didn't have a worry in the earth. In fact, I was outset to recall that it wasn't going to be difficult at all for me to grow upward. But just when things were really looking good for me, something happened. I got mixed upward with a agglomeration of monkeys and all of my happiness flew right out the window. Those monkeys all merely collection me out of my mind.

If I had kept this monkey problem to myself, I don't call up it would have amounted to much; only I got my grandpa mixed up in information technology. I felt pretty bad almost that because Gramps was my pal, and all he was trying to do was assistance me.

I even coaxed Rowdy, my old bluetick hound, into helping me with this monkey trouble. He came out of the mess worse than Granddaddy and I did. Rowdy got so disgusted with me, monkeys, and everything in general, he wouldn't even come out from nether the house when I called him.

Information technology was in the belatedly 1800s, the best I tin recollect. Anyhow—at the time, we were living in a make-new country that had just been opened up for settlement. The subcontract we lived on was chosen Cherokee state because information technology was smack dab in the centre of the Cherokee Nation. It lay in a strip from the foothills of the Ozark Mountains to the banks of the Illinois River in northeastern Oklahoma. This was the last identify in the earth that anyone would expect to find a bunch of monkeys.

I wasn't much bigger than a young possum when Mama and Papa settled on the land; but afterward I grew up a little, Papa told me all nearly it. How he and Mama hadn't been married very long, and were sharecropping in Missouri. They were unhappy, too; because in those days, being a sharecropper was but near as bad as existence a hog thief. Everybody looked down on you.

Mama and Papa were young and proud, and to have people look down on them was almost more than they could stand. They stayed to themselves, kept on sharecropping, and saving every dollar they could; hoping that someday they could buy a farm of their own.

Just when things were looking pretty skillful for Mama and Papa, something happened. Mama hauled off and had twins—my little sister Daisy and me.

Papa said that I was born start, and he never s

aw a healthier boy. I was as pink equally a sunburnt huckleberry, and every bit lively as a young squirrel in a corn crib. Information technology was different with Daisy though. Somewhere along the line something went wrong and she was born with her correct leg all twisted up.

The md said at that place wasn't much incorrect with Daisy's erstwhile leg. It had something to do with the muscles, leaders, and things like that, being all tangled up. He said in that location were doctors in Oklahoma Urban center that could take a crippled leg and straighten it out as straight as a ramrod. This would toll quite a bit of coin though; and money was the one affair that Mama and Papa didn't have.

Mama cried a lot in those days, and she prayed a lot, also; only nothing seemed to do whatever skillful. It was bad enough to be stuck there on that sharecropper'due south farm; but to accept a lilliputian daughter and a twisted leg, and not be able to practise anything for her, injure worst of all.

And so one day, right out of a clear blue sky, Mama got a letter from Grandpa. She read information technology and her face turned equally white every bit the bawl on a sycamore tree. She sat right down on the dirt floor of our sod firm and started laughing and crying all at the same fourth dimension. Papa said that afterward he had read the alphabetic character, it was all he could do to keep from bawling a little, too.

Grandpa and Grandma were living down in the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma. They owned one of those big old country stores that had everything in it. Grandpa wasn't only a storekeeper; he was a trader, besides, and a good one. Papa always said that Grandpa was the merely honest trader he ever knew that could trade a terrapin out of its crush.

In his letter, Grandpa told Mama and Papa that he had done some trading with a Cherokee Indian for sixty acres of virgin land, and that it was theirs if they wanted information technology. All they had to practice was come downwards and brand a subcontract out of it. They could pay him for it whatever way they wanted to.

Well, the way Mama was carrying on, at that place wasn't simply one thing Papa could do. The side by side morning, before the roosters started crowing, he took what money they had saved and headed for town. He bought a team of big red Missouri mules and a covered railroad vehicle. Then he bought a turning plow, some seed corn, and a milk cow. This took about all the money he had.

It was way in the dark when Papa got back dwelling. Mama hadn't even gone to bed. She had everything they owned packed, and was ready to get. They were both so eager to become away from that sharecropping farm that they started loading the railroad vehicle by moonlight.

The concluding matter Papa did was to make a ii-infant cradle. He took Mama'due south former washtub and tied a short slice of rope to each handle. To give the cradle a petty bit of bounciness, he tied the ropes to two cultivator springs and hung the whole contraption to the bows within the covered wagon.

Mama thought that old washtub was the all-time baby cradle she had ever seen. She filled it about half full of corn shucks and quilts, and and so put Daisy and me downwards in it.

After taking one terminal look at the sod business firm, Papa cracked the whip and they left Missouri for the Oklahoma Territory.

When Papa told me that office of the story, he laughed and said, "If anyone ever asks you how y'all got from Missouri to the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, y'all only tell them that you rode a washtub every inch of the fashion."

The day they reached Gramps'south store, Papa was only virtually all in and had his mind attack sleeping in one of Grandma's feather beds. Mama wouldn't mind to that kind of talk at all. She had waited so long for a subcontract of her ain, she was bound and determined to spend that night on her ain land.

Grandma tried to talk some sense into Mama. She told her that the land was only iii miles down the river, and it certainly wasn't going to run away. They could stay all dark with them, residue upward, and continue the next day.

Mama puffed upward like a settin' hen in a hailstorm. Nothing Grandma or Grandpa said inverse her mind. She told Papa that he could stay in that location if he wanted to, she'd just take Daisy and me and continue by herself.

Papa knew meliorate than to open his rima oris, because in one case Mama had fabricated up her heed similar that, she wouldn't accept budged an inch from a buzzing rattler. In that location wasn't but one thing he could exercise. He just climbed back in the wagon, unwrapped the check lines from the brake, and said, "Get up!" to those old Missouri mules.

It was in the twilight of evening when Mama and Papa reached the country of their dreams. They camped for the dark in a grove of tall white sycamores, correct on the banking concern of the Illinois River.

Papa said that as long every bit he lived, he would never forget that night. It seemed to him that they were existence welcomed by every living matter in those Cherokee bottoms. Whippoorwills were calling, and nighttime hawks were crying every bit they dipped and darted through the starlit heaven. Bullfrogs and hoot owls were jarring the ground with their deep voices. Even the little speckled tree frogs, the katydids, and the crickets were chipping in with their nickel's worth of welcome music.

A big grinning Ozark moon crawled up out of nowhere and seemed to say, "How-do-you-do, neighbour! I've been looking for you. Information technology gets kind of lonesome out here. Welcome to the land of the Cherokee!"

Papa said Mama was so taken in by all of that beauty, she seemed to exist hypnotized. She only stood at that place in the moonlight with a warm footling smile on her face, staring out over the river, her black eyes glowing like black haws in the morning dew. Finally, she gave a deep sigh, simply as if she had dropped something heavy from her shoulders. Then spreading her arms out wide, she said in a low voice, "Information technology'south the work of the Lord—that's what it is. Just think—all of this is ours—sixty acres of it."

Papa said he was feeling then good that he felt he could have walked right out on the waters of the river just as Jesus did when he walked on the waters of the ocean.

Mama was a little adult female, barely tipping the scales at a hundred pounds; but what she lacked in height and weight, she made upwardly in force and spirit. Pulling her finish of a crosscut saw, and swinging the heavy blade of a double-bitted ax, she helped Papa clear the country.

Papa permit Mama choice the spot for our log house. This wasn't an piece of cake chore for her. She walked all over that sixty acres, looking and looking. Finally, she constitute the very spot she wanted and put her foot downwardly. It was in the foothills overlooking the river bottoms, in the rima oris of a blue footling canyon.

I grew upwards on that Cherokee farm and was just about as wild as the gray squirrels in the sycamore trees, and every bit gratuitous as the red-tail hawks that wheeeeed their cries in those Ozark skies. I had a cracking knife, and a darn skillful dog; that was about all a boy could hope for in those days.

My piffling sister Daisy grew up, too; but not like I did. It seemed as if that former leg of hers held her growing back. Each year it got worse and worse. The foot function kept twisting and twisting, until finally she couldn't walk on information technology at all. That's when Papa fabricated a crutch for her out of a red oak limb with a fork on one end. The fashion Daisy could nothing around on that old habitation-made crutch was something to see. She could become around on it just about too as I could on two straight legs.

Information technology was always a mystery to me how my picayune sister could be so happy, and and then total of life with an erstwhile twisted leg like that. She was always laughing and singing and hopping around on that old crutch only as if she didn't have a worry in the globe. Her one big delight was in getting me all riled up by poking fun at me. She never overlooked an opportunity, and it seemed that these opportunities came about every fifteen minutes.

Up on the hillside from our house, nether a huge cherry oak tree, Daisy had a playhouse. From early jump until late autumn, practically all of her time was spent there.

I didn't like to mess effectually Daisy's playhouse. Every time I went up in that location, I had a guilty feeling—similar maybe I shouldn't be at that place. She had all kinds of girl stuff setting around; corn shuck dolls, mud pies, and pretty bottles. She treasured every tin can that came to our home. In each one, some kind of wild bloom peeked out.

At one stop of her playhouse, Daisy had built a little altar. She had made a cross by tying ii grapevines together and covering them with tinfoil. The face of Christ was there, as well. Daisy had molded it from crimson clay. For the eyes, she had pressed blue shells from a hatched-out robin'south nest into the soft cla

y. She had covered the crown with moss to resemble hair. When Mama discovered that the moss was actually growing in the soft clay, she told everyone in the hills most it. People came from miles around to see the miracle. I never saw anything like it.

It was pretty around Daisy's playhouse; especially, in the early on spring when the dogwoods, redbuds, and mountain flowers were blooming. Warm lilliputian breezes would whisper downward from the dark-green, rugged hills; and the air would be and then full of sweet smells, information technology would brand your olfactory organ tickle and burn down. If you closed your optics, and filled your lungs full of that sweet-smelling stuff, your head would get as light every bit a hummingbird's plume and experience as if it was going to canvas away past itself.

Daisy was never alone in her playhouse. She had all kinds of little friends. Large fat bunnies, red squirrels, and chipmunks would come right upwards to her and eat from her mitt. She wouldn't be in her playhouse five minutes until all kinds of wild birds would come up winging in from the mountains. They would sit effectually in the bushes and sing and so happy and loud that the mountains would band with their birdie songs. Sometimes they would even lite on her shoulders.

I never could empathise how my little sister made friends with the birds and the animals. I couldn't get inside a mile of anything that had hair or feathers on information technology. Daisy said it was because I was a male child and was catching things all the time.

One morning in the early leap, Papa came in from doing the chores with an empty milk bucket in his hand. He looked grouchy, and didn't even say "Good morn" to whatsoever of u.s.. This was then unusual that correct away Mama knew something was wrong.

From the melt stove where she was fixing our breakfast, Mama smiled and said, "Knowing how desperate y'all are to go the planting washed, I'd say it was going to rain."

"No," Papa said, in a disgusted voice. "Information technology's non going to rain. Emerge Gooden's gone again."

Emerge Gooden was our crazy one-time milk moo-cow.

ortizsobjecold1950.blogspot.com

Source: https://onlinereadfreenovel.com/wilson-rawls/33992-summer_of_the_monkeys.html

0 Response to "Summer of the Monkeys Read Online Pdf"

Post a Comment